There are many ways to write “cross-platform” apps - ranging from going all-in on the cross-platform idea and writing a web app in something like Electron, to writing two completely separate apps that happen to look the same and do the same thing. And of course, the internet is full of… let’s say “vibrant” discussion on what’s the best way to do things.

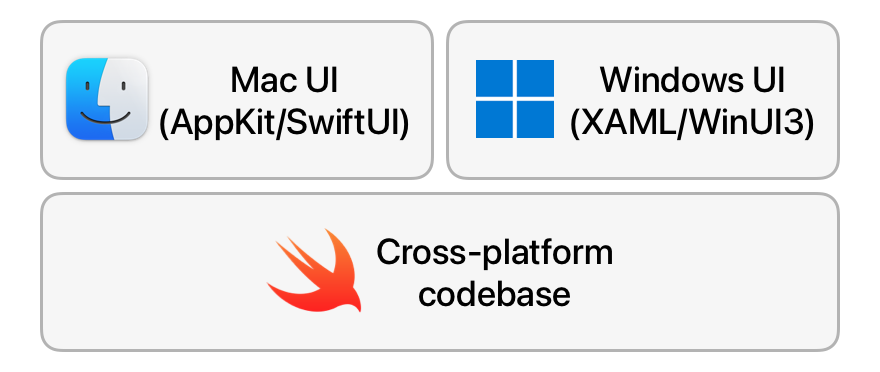

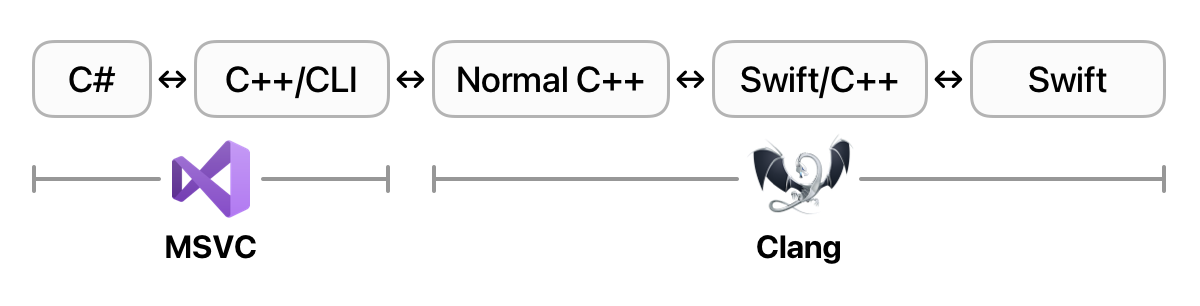

My personal preference is to write the UI layer in a native technology stack in order to take advantage of a particular platform’s look-and-feel, with the “core” logic in a cross-platform codebase that the native layer can interact with. In an ideal world, we’d be able to implement this incredibly complex tech stack:

A drawback of this approach is that it does tend to limit your choice of programming languages for the cross-platform codebase. Programming languages all tend to have their own ABIs, and you need to rely on there being a “bridge” available between the two languages you want to use. In practice, this often means finding an intermediate ABI that both languages can interoperate with - quite a lot of languages have compatibility with the C ABI, for instance.

Since I primarily work on Mac and iOS apps, I write code in Swift every day. It’s been getting a lot more love on the cross-platform front than its predecessor in the ecosystem, Objective-C (Swift even has official Windows builds!), and it’d be great if we could ship CascableCore in Swift to multiple platforms.

However, the challenge comes not necessarily from compiling our Swift code on Windows, but from using it from other languages. Specifically in this case, I’d like to write a C# app using WinUI 3 that uses our CascableCore camera SDK. However, there just isn’t an existing bridge between Swift ABI and the C#/CLR one.

Well, maybe there’s a solution. Swift recently introduced C++ interoperability… maybe we could use that to bridge between the two worlds?

How hard could it be?

That little question, dear reader, led me down quite the rabbit hole. This blog post is a brave re-telling of that story, tactfully omitting the defeats and unashamedly embellishing the victories — just as any story worth its salt does.

If you already know what C++/CLI and a CLR is and don’t need my life story, you can hop straight over to the SwiftToCLR proof-of-concept repository. The readme there is still pretty long, but it’s a more technical document with the aim of getting folks more familiar with the technologies at hand to get stuck in.

Otherwise, stick around! It’s been a… journey. An exciting, fun, frustrating, tedious journey. However, I learned a lot, and hopefully you’ll enjoy coming along for the ride.

What Are We Trying To Achieve?

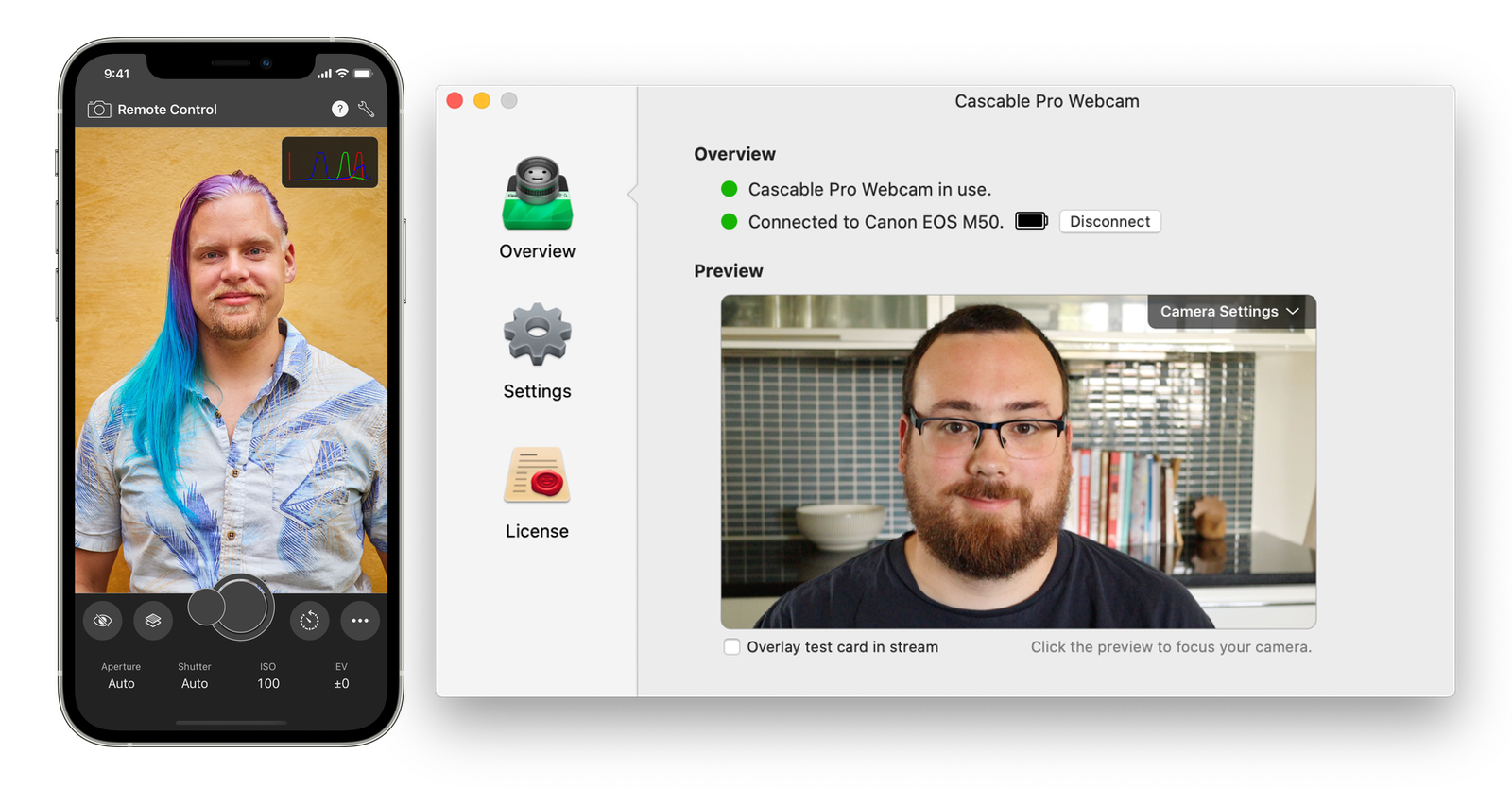

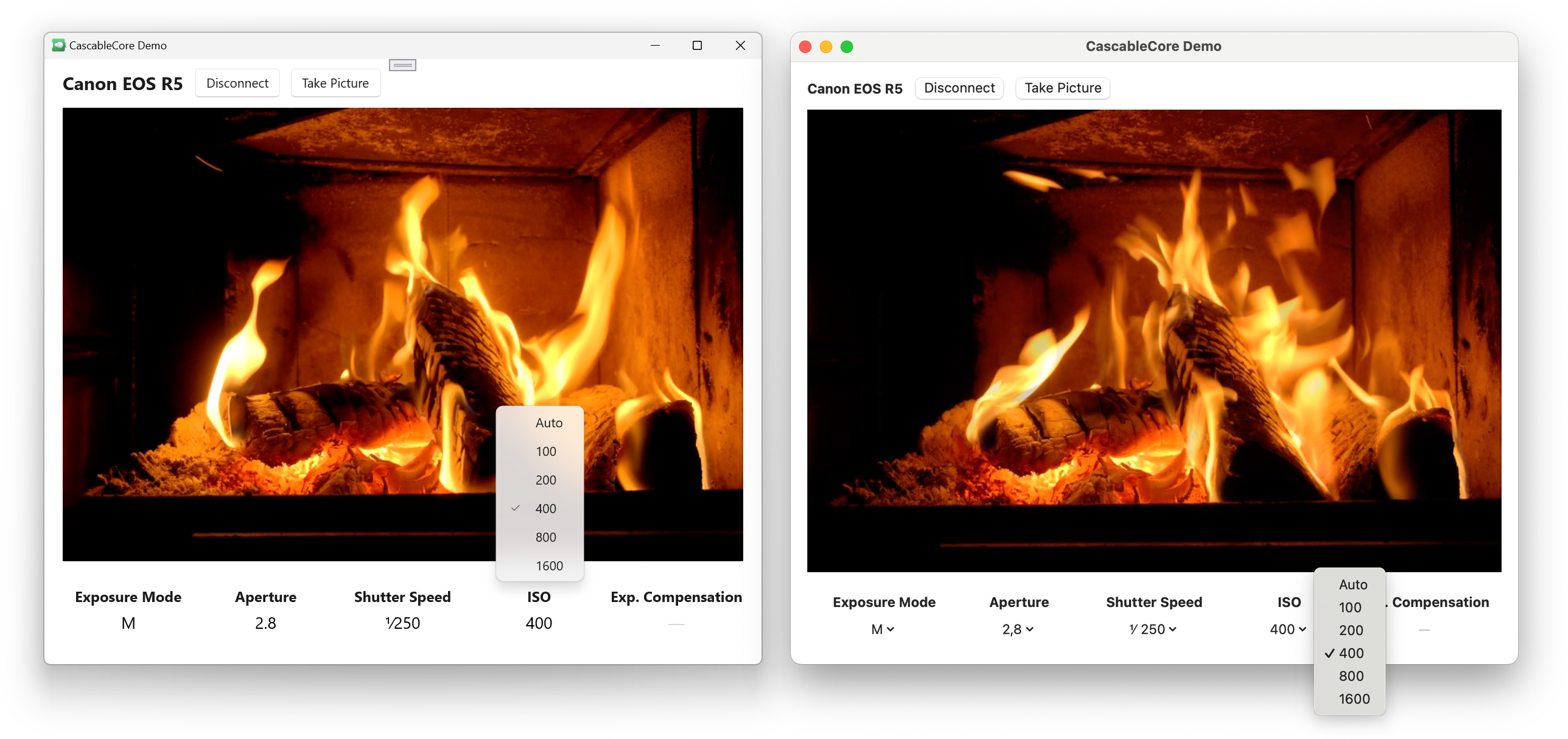

My company has an SDK called CascableCore, which talks to cameras from various manufacturers (such as Canon, Nikon, Sony, etc) via the network or USB. Its job is to deal with each camera’s particular protocols and oddities as it presents a unified set of APIs to apps that use the SDK. This SDK is used by our own apps, as well as those from a number of third-party developers.

There’s nothing particularly platform-specific about this task — networks and USB are cross-platform by design — so CascableCore is a great candidate to be a cross-platform codebase. It’d give us the option to expand our apps to more platforms in the future, as well as expand the potential customer base for the SDK itself.

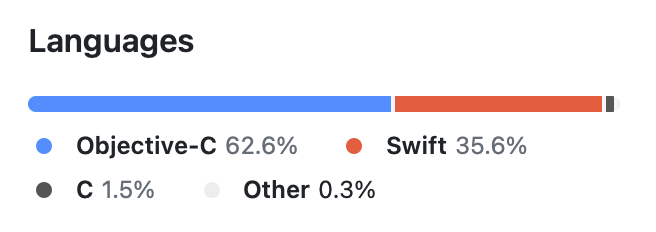

CascableCore’s codebase currently looks like this — a bunch of Objective-C and some Swift. All new code is written in Swift, but still — there’s a hefty amount of Objective-C in there:

Despite its GNU roots, Objective-C isn’t particularly multi-platform in the real world, so no matter what we do we’ll be rewriting a significant amount of code to go multi-platform — and, rationally speaking, C++ is probably not a bad choice. We could do that RIGHT NOW.

However, dear reader, I’ll let you in on a little secret if you promise not to tell anyone. Lean closer. Ready?

…I hate C++.

Don’t tell anyone, OK?

My dislike of C++ is, if I’m honest, mostly irrational — I’ve just seen one horrendous C++ template too many. But, we could just… not do that in our own code, y’know?

On the more rational side, though, we are a small company and our expertise is largely in Swift simply as a consequence of only having Mac and iOS apps at the moment. We’ve already dabbled in Swift on other platforms, too — Photo Scout’s backend is written in Swift/Vapor running on Linux servers, and it’s been a great success. Since most of CascableCore’s work is platform-agnostic, once the initial work is done we can (in theory) use our existing Swift expertise to maintain and improve CascableCore with only a relatively small additional cross-platform maintenance overhead.

And… since we’re being honest, it’s just plain fun to explore new technologies, especially in more esoteric ways. Even if we don’t end up shipping CascableCore in Swift on Windows, I learned a lot and (largely) had fun doing it. What’s the downside?

Anyway, I’d being keeping half an eye on the Swift on Windows story over the past few months/years until a few months ago this post on Mastodon pulled on a thread in my brain:

This ended up being a perfect storm of circumstances:

- Swift on Windows seems to be decently viable now.

- Swift had recently introduced the C++ interoperability feature, opening up possibilities for interacting with other languages.

- I like to slow down a little and do interesting/”hack day” projects in December.

- I really wanted a reason to justify getting a Framework laptop.

Not long later, my Framework laptop arrived and I was off to the races — a two-week timebox to explore this as I wind down for the Christmas break? Heck yeah.

I, er, went a little overboard on the unboxing photos.

The Proof-of-Concept Project

When putting together projects like this, it’s always nice to be able to use “real” code. Luckily, we have the CascableCore Simulated Camera project, which is a CascableCore plugin that implements the API without needing a real camera to hand. This is a perfect candidate for this project — it’s implementing a real, shipping API without the need for us to figure out network or USB communication on Windows. It’s everything we need and nothing we don’t. Also, happily, it’s already all in Swift.

What isn’t in Swift, unfortunately, is the CascableCore API itself. It was introduced before Swift, and has remained a set of Objective-C headers to this day. We’ll need to redefine these in Swift. Oh, and port StopKit, which is an Objective-C dependency.

Finally, we need a little bit of glue. CascableCore “proper” has a central “camera discovery” object that implements USB and network discovery, along with interfacing with plugins such as the simulated camera. We’re not bringing that over to the Windows proof-of-concept, so we need something in its place so we can actually “discover” our simulated camera on Windows.

Getting all this into place took a few days — the simulated camera was largely fine other than needing to remove some Objective-C features (such as Key-Value Observing) and use of Apple-only APIs (such as CoreGraphics). Porting StopKit and rebuilding the Objective-C API protocols into Swift ones took a couple of days, and the glue at the end a day or so.

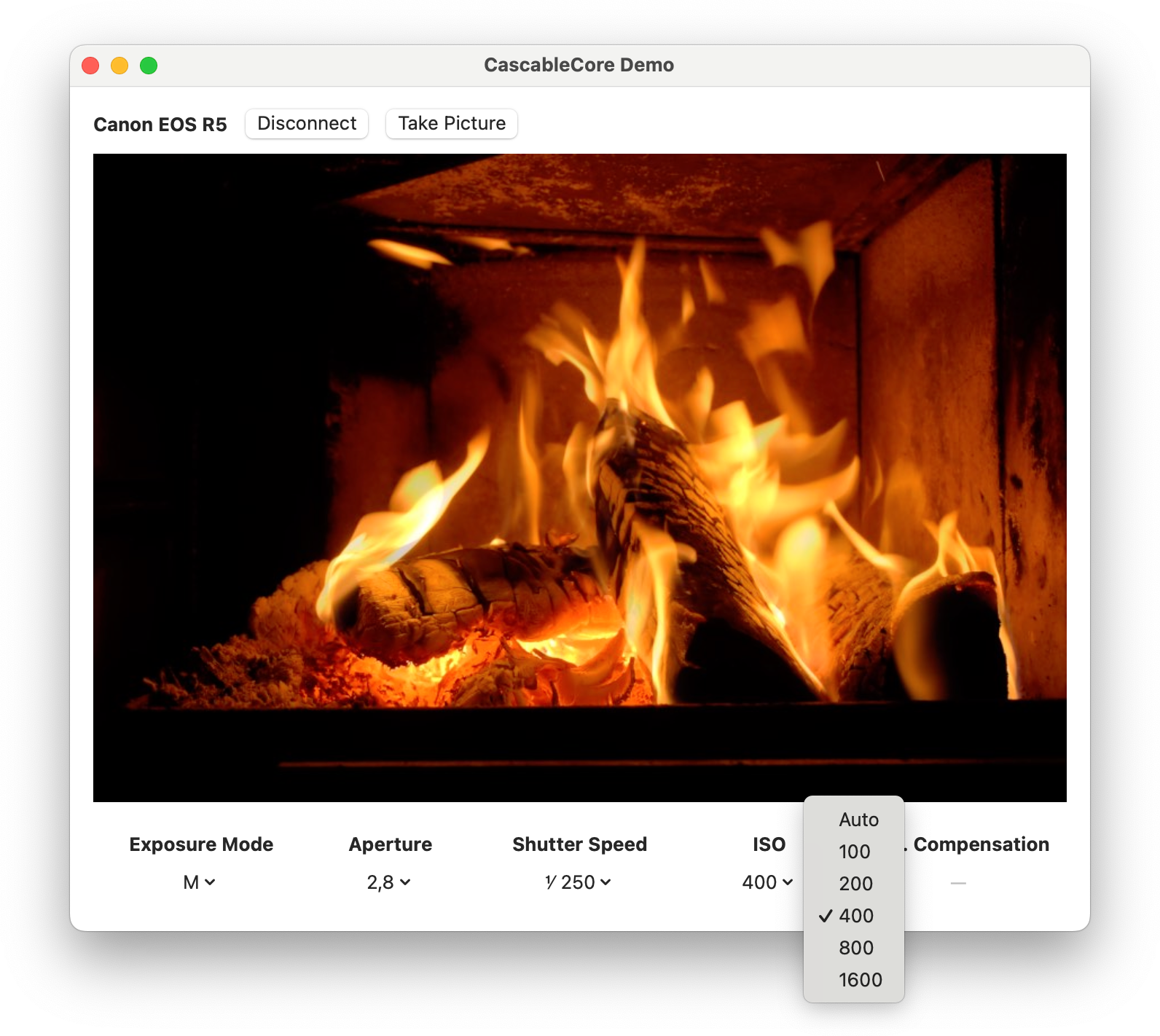

Let’s have a look at a little demo project on the Mac:

This little app discovers and connects to a camera, shows the camera’s live view feed, shows some camera settings, and lets you change them. It’s a simple enough app, but implements a decent chunk of the CascableCore API: issuing camera commands, observing camera settings, and receiving a stream of live view images. If we can get this working on Windows, we can get everything working.

Let’s try to build this demo app on Windows!

Figuring Out The Core Problem

The first step is to get the Swift code compiling on Windows, which was easy enough in our case (see above). The next is to instruct the Swift compiler to emit C++ headers for our targets:

swiftSettings: [

.interoperabilityMode(.Cxx),

.unsafeFlags(["-emit-clang-header-path", ".build/CascableCoreSimulatedCamera-Swift.h"])

]I will note that the Swift Package Manager doesn’t officially support emitting C++ headers yet, hence the clunky unsafe build flag. This has been working fine for me, but the official way to do this is via another build system such as CMake.

At any rate, we now have a C++ header for calling into our Swift code! Now to Google “Calling C++ from C#” and… ah.

Telling the story of two days of Googling would be exquisitely boring, so I’ll skip ahead to why this is actually rather difficult after a quick foray into runtimes.

A Rumble of Runtimes

A runtime can be thought of as a “support structure” for your code, providing functionality at runtime like memory management, thread management, error handling, and more. Swift, for instance, uses ARC (Automatic Reference Counting) for memory management, and the runtime is the thing that actually does the allocation, reference counting, and deallocation of objects.

C# runs in the CLR (Common Language Runtime), which is a garbage-collected runtime that’s a lot more complex than the Swift one, providing additional things like just-in-time compiling.

The thing about a runtime - especially the more complex ones like the CLR - is that they need everything in the “bubble” they operate to conform to the same rules for everything to work correctly. The CLR’s garbage-collection works because all of the objects in there are laid out in a particular way and behave the same way. A random Swift object floating around inside the CLR wouldn’t be able to take part in garbage collection since the compiled Swift code has no knowledge of such a thing — and the converse is true, too: a random C# object floating around inside the Swift runtime wouldn’t be able to take part in ARC since it don’t have the ability to call the Swift runtime’s reference-counting methods.

There are two ways around this: exiting the bubble entirely and doing things manually, or “teaching” another language about your runtime.

Most runtimes do tend to have a way of “exiting” the bubble. C# calls this unsafe code, and Swift has a number of withUnsafe… methods. When in unsafe code, your memory management guarantees are gone (or exist in a very limited scope) and you, the programmer, are responsible for dealing with memory management yourself.

However, Swift’s C++ interop feature is pretty neat in that it actually, in a way, “teaches” C++ about Swift’s memory management. The Swift C++ interop header for the tiniest of tiny examples is what I describe as “5000 lines of chaos” - lots of imports and macros and templates that form a bridge from C++ into the Swift runtime, allowing you to use Swift objects directly in C++ while still taking part in ARC. Great!

The CLR also has a way of teaching C++ about the CLR’s memory management in the form of a special “dialect” of C++ called C++/CLI. Great!

Well…

Why This Is Actually Rather Difficult

We’re finally getting down to the core of the problem here. Let’s lay out some facts, including a couple more that I discovered during that two days of excruciatingly boring Googling mentioned above:

-

Swift’s C++ headers contain a lot of additional infrastructure that “teaches” C++ about Swift’s memory management.

-

NEW FACT! Swift’s C++ headers have a lot of

Clang-specific features in them, to the point where they requireClangto build against them. -

C++/CLI is a special dialect of C++ containing additional infrastructure that “teaches” C++ about the CLR’s memory management.

-

NEW FACT! C++/CLI can only be compiled by

MSVC, the Microsoft Visual C++ compiler (or perhaps more accurately -Clangcan’t compile C++/CLI).

This is a little bit like those party games where everyone makes a statement about someone else and you have to combine everything to figure out who’s lying. If you haven’t managed that yet:

-

MSVCcan’t compile the Swift C++ interop header. -

Clangcan’t compile C++/CLI. -

This means that we can’t create a C++/CLI wrapper from our Swift C++ interop header.

Crap.

Luckily, Clang’s compiled output is (at least somewhat) ABI-compatible with MSVC, so although MSVC can’t compile the Swift C++ interop header, it can link against the compiled output.

This, thankfully, opens a route through — we can make an additional wrapper layer, compiled with Clang, that wraps the generated Swift/C++ APIs in, er… I guess… “normal?” C++ that MSVC can deal with. The end-to-end chain would then be:

While this is a chain of four steps, we thankfully “only” need two wrappers:

-

We have our Swift code that’s compiled by

Clang, giving us a compiled binary and a C++ header. -

Wrapper 1: Compiled by

Clang, wraps theClang-generated Swift C++ interop header with a “normal” C++ one thatMSVCcan understand. The wrapper implementation calls the API defined in the C++ interop header. -

Wrapper 2: Compiled by

MSVC, wraps the “normal” C++ header with a C++/CLI one that gets us into the CLR, and therefore up to C#. The wrapper implementation calls the API defined in Wrapper 1. -

We have our C# code, compiled by

MSVC, running in the CLR. It calls the API defined in Wrapper 2.

This isn’t actually that difficult - it’s just very tedious. Each link in the chain has its own types, and they need to be translated in both directions (i.e., a C# string needs to end up as a Swift String when calling a method, then a Swift String being returned needs to end up as a C# string on the way back).

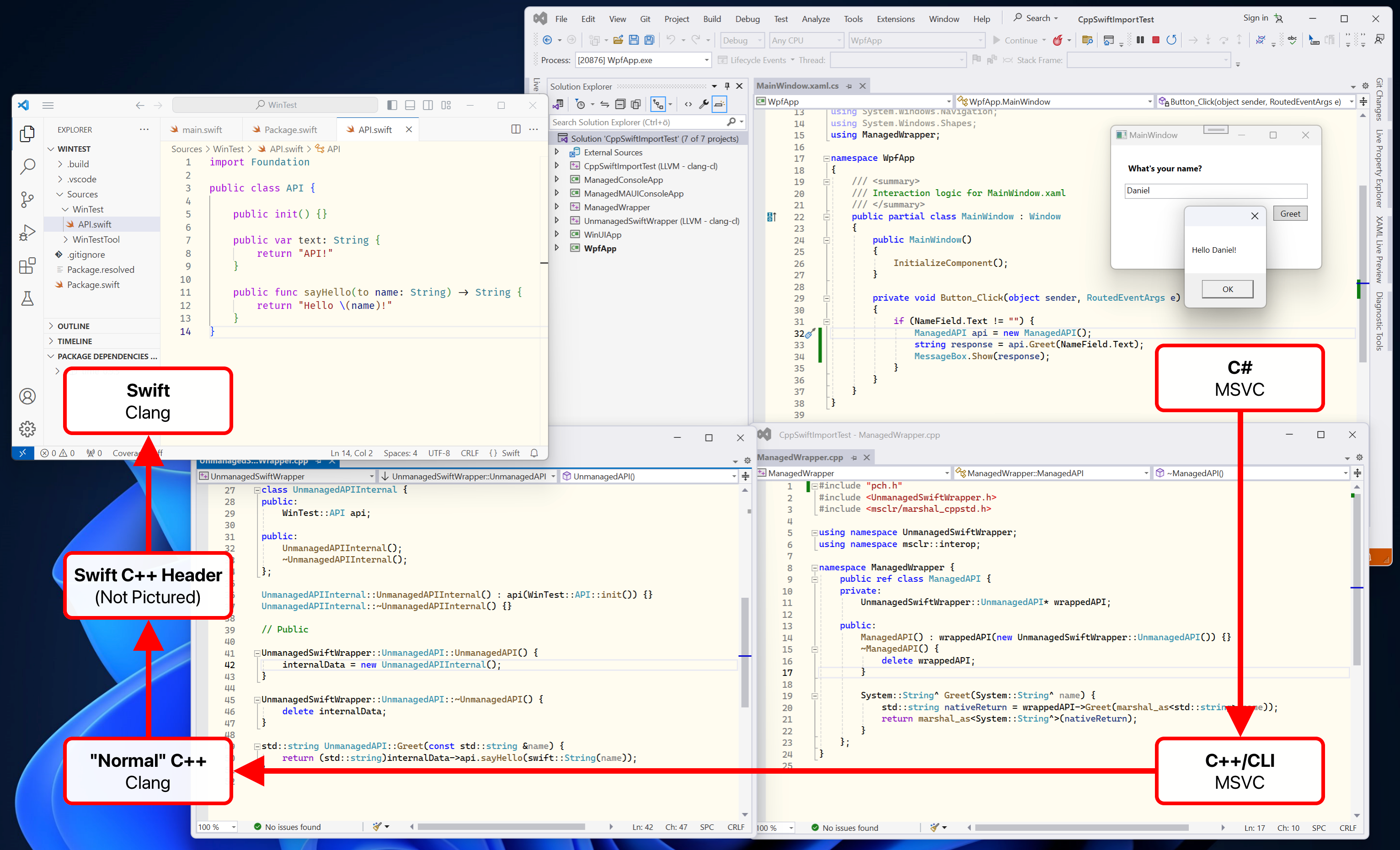

A simple, manually-made test project ends up looking like this:

It’s not pretty, but it works!

Making This Not Suck

Manually building two wrapper layers is, well, kind of a pain. For CascableCore it’d actually largely be a one-off cost — the API is fairly mature and stable, and we try not to change it unless we have to. Still, not fun.

Our case is fairly rare, though. Having to adjust two wrapper layers for every change you make as you work on Swift code is annoying enough to make you give up and not bother, so what can we do to make this better?

If you study the snippets of code in the screenshot above, a fairly strong pattern emerges even from such a small example.

For each “level”, we need to:

-

Make a class that holds a reference to an object from the level below,

- For each method on that wrapped class, have a corresponding method in the wrapper that:

- Takes appropriate parameters for the method being wrapped,

- Translates them all into types appropriate for the level below,

- Calls the wrapped method with the translated parameters,

- If needed, translates the returned value into a type appropriate for the current level and returns it.

- …there’s no step three!

That’s extremely repetitive and well-defined work, and it’s a perfect candidate for…

…drumroll please…

Automated code generation!

Introducing SwiftToCLR

SwiftToCLR is the main “result” of this proof-of-concept project, and the thing that took by far the most amount of time and trouble. I’ll spare you the journey here, but if you’re interested in it there’s a more detailed discussion over on the project’s GitHub repository.

SwiftToCLR is a command-line tool, written in Swift, that takes your C++ interop header from Swift (as well as a couple of other bits and pieces) and generates the header and implementation for both wrapper layers discussed above. The example usage here is on Windows, but it does work on macOS too.

Note: You may start to notice mentions of “unmanaged” and “managed” code here and there. This is a result of the project’s focus on the CLR — “managed code” is how the CLR refers to code running within the garbage-collected runtime, and “unmanaged code” is code running outside of that environment.

C:\> .\SwiftToCLR.exe CascableCoreBasicAPI-Swift.h

--input-module CascableCoreBasicAPI

--cxx-interop .\swiftToCxx

--output-directory .

Using clang version: compnerd.org clang version 17.0.6

Successfully wrote UnmanagedCascableCoreBasicAPI.hpp

Successfully wrote UnmanagedCascableCoreBasicAPI.cpp

Successfully wrote ManagedCascableCoreBasicAPI.hpp

Successfully wrote ManagedCascableCoreBasicAPI.cpp

C:\>Since this was a timeboxed project, right now it only generates the source files (which can be compiled with Visual Studio by setting up a couple of simple targets). The most immediate and high-impact improvement to SwiftToCLR would be to extend it to actually build them too — just a single command to get compiled binaries to dump into your C# project would be amazing.

Let’s have a quick look at the layers here. Given the following Swift example:

public class APIClass {

public init() {}

public var text: String { return "API!" }

public func sayHello(to name: String) -> String {

return "Hello from Swift, \(name)!"

}

public func doOptionalWork(optionalString: String?) -> String? {

if optionalString == nil {

return "I did some work"

} else {

return nil

}

}

}The Swift/C++ interop header will be over 5000 lines. Here’s an excerpt of our class’ definition in there:

class SWIFT_SYMBOL("s:9BasicTest8APIClassC") APIClass : public swift::_impl::RefCountedClass {

public:

using RefCountedClass::RefCountedClass;

using RefCountedClass::operator=;

static SWIFT_INLINE_THUNK APIClass init() SWIFT_SYMBOL("s:9BasicTest8APIClassCACycfc");

SWIFT_INLINE_THUNK swift::String getText() SWIFT_SYMBOL("s:9BasicTest8APIClassC4textSSvp");

SWIFT_INLINE_THUNK swift::String sayHello(const swift::String& name) SWIFT_SYMBOL("s:9BasicTest8APIClassC8sayHello2toS2S_tF");

SWIFT_INLINE_THUNK swift::Optional<swift::String> doOptionalWork(const swift::Optional<swift::String>& optionalString) SWIFT_SYMBOL("s:9BasicTest8APIClassC14doOptionalWork2of14optionalStringSSSgAA0F4TypeO_AGtF");

// (Various internal and private definitions skipped)

};Given this header, SwiftToCLR will output the following “normal” C++ wrapper:

class APIClass {

public:

std::shared_ptr<BasicTest::APIClass> swiftObj;

APIClass(std::shared_ptr<BasicTest::APIClass> swiftObj);

APIClass();

~APIClass();

std::string getText();

std::string sayHello(const std::string& name);

std::optional<std::string> doOptionalWork(const std::optional<std::string>& optionalString);

};…and the following C++/CLI wrapper:

public ref class APIClass {

internal:

UnmanagedBasicTest::APIClass *wrappedObj;

APIClass(UnmanagedBasicTest::APIClass *objectToTakeOwnershipOf);

public:

APIClass();

~APIClass();

System::String^ getText();

System::String^ sayHello(System::String^ name);

System::String^ doOptionalWork(System::String^ optionalString);

};I won’t paste the entire implementation here, but here’s an example from the “normal” layer in which we’re translating optional strings in both directions. The code is particularly verbose here, but given it’s autogenerated code that is unlikely to ever be looked at, I think that’s alright.

std::optional<std::string> UnmanagedBasicTest::APIClass::doOptionalWork(const std::optional<std::string> & optionalString) {

swift::Optional<swift::String> arg0 = (optionalString.has_value() ? swift::Optional<swift::String>::init(*(swift::String)optionalString) : swift::Optional<swift::String>::none());

swift::Optional<swift::String> swiftResult = swiftObj->doOptionalWork(arg0);

if (swiftResult) {

swift::String unwrapped = swiftResult.get();

return std::optional<std::string>((std::string)unwrapped);

} else {

return std::nullopt;

}

}So… great, right?! Let’s go! Wait… more roadblocks?

Limitations of Swift’s C++ Interop

The keen-eyed amongst you may have noticed that in my usage example above, I was giving SwiftToCLR a header file called CascableCoreBasicAPI-Swift.h. Why a “basic” API?

Swift’s C++ interop feature is still pretty young, and has a number of limitations that directly impact our CascableCore API. There’s a deeper discussion in the readme on the project’s GitHub repository, but the three that impact us the most are:

-

Protocols aren’t exposed through C++. CascableCore’s API is almost entirely defined in protocols.

-

Swift’s

Datatype isn’t exposed through C++. We useDatato hand image data over to client apps, including frames of the live view stream. -

Swift closures aren’t exposed through C++. This is a huge one - CascableCore’s API uses callbacks extensively since working with cameras is intrinsically asynchronous. They’re used to observe changes to camera settings, receive frames of the live view stream, find out if a sent command was successful, and more.

So, what to do? All of these problems do have workarounds, with the closure limitation being particularly gnarly to combat. After a bit of pondering, I decided that they were outside of the scope of this project (especially considering the timebox I had). This is a long-term endeavour, and hopefully Swift’s C++ interop featureset will improve over time.

Instead, I built the “CascableCore Basic API”, which is a simplified API that wraps the “full” one (this project is full of wrappers, crikey):

-

Objects are defined as classes rather than protocols.

-

Dataobjects in Swift are exposed as “unsafe” methods to copy the data to a pointer viaData’scopyBytes(to:count:)method. -

There are no callbacks/closures. To find changes, you need to poll (boooo!).

It’s clunky, but it works!

Holy Crap Are We Finally Writing C#?

I have to admit, there were times where I thought I’d have to abandon this project. A month into my two week timebox, every corner I turned brought up a new problem. Some clear and understandable (“Oh wait, optionals!”), others less so (“Why does this code run fine in a swift test but crash when called from C#?”).

However, one day everything finally “clicked” and suddenly this demo app was coming together fast. Holy crap, it works!!

I tried to write the demo app as I should, so I abstracted away the polling (boooo!) with a couple of classes — PollingAwaiter and PollingObserver — that vend events for the app to observe as if the polling limitation wasn’t present.

Otherwise, the Windows demo app is pretty bog-standard, which is exactly what I hoped the outcome would be. It’s written in C# using XAML and WinUI 3 for the UI, and the whole thing is a standard Visual Studio app project. There’s nothing special about it at all, other than having to link to Swift.

Hiding under this boringness are a trove of unanswered technical questions. Again, these are discussed more in the project’s GitHub repository, but some of the larger ones:

-

Why do we get very weird crashes when our Swift code is built for static linking? (Sidebar: You really must explicitly mark your targets as

.dynamicin your package manifest to get SPM to build dynamic binaries (i.e.,.dllfiles), otherwise you’ll lose days to chaos as I did.) -

How do we best solve the problem of the lack of closures?

-

What’s the real-world performance impact of translating every parameter through two wrapper layers?

System::String→std::string→swift::Stringand back is hardly ideal — especially when arrays get involved — and I didn’t have to time to run meaningful performance measurements. -

When run in this context (i.e., a C# app managing the process’ lifecycle), Swift code doesn’t get a working main dispatch queue (or runloop, or…). This is largely expected (

dispatch_get_main_queue()has some relevant notes in its documentation), but it’d be very useful to be able to sync the C# app’s UI thread with the main dispatch queue.

Conclusion

So, what became of this experiment? Well, I did manage to build the same app on macOS and Windows with the same underlying Swift codebase, which I’m incredibly happy about!

I’ve learned a ton, and I feel like I now have a reasonably well-informed opinion of Swift on Windows (which was the primary “business” goal of this project, I suppose).

Swift is undoubtedly an “Apple platforms-first” language, particularly the tooling. Like with Swift on Linux, we get a second-class Foundation (although that’s actively being worked on right now). The Swift plugin for Visual Studio Code works on Windows and is pretty great, if it wasn’t for the fact that no matter what I try, sourcekit-lsp.exe continuously spins at 100% CPU usage unless I disable code completion. Building our project with SPM’s default configuration gives a ton of .o files to manually assemble, only to get inscrutable crashes deep in the runtime (explicitly flagging everything to be a .dynamic library fixes both of these).

On all platforms, the Swift/C++ interop feature set is extremely limited — the lack of closures in particular is a particularly big one. That polling workaround I implemented will not make it to production.

However.

None of that changes the fact that once I’d overcome these hurdles, I was able to take a Swift codebase that can be compiled for iOS, macOS, and Windows and build a meaningful demo project in C# on top of it in just a couple of days. Once it’s up-and-running, it’s amazing.

We don’t be dropping everything to build Windows versions of CascableCore and our apps just yet — we have a lot of other work on our plate. However, my experience was very confidence-inspiring, and I can genuinely see a path to shipping real products to real users using a cross-platform CascableCore and this hybrid C#/Swift approach.

I’m also very excited about the future of Swift on Windows, and will be staying up-to-date with what’s going on. There’s also a number of meaningful improvements that can be made to SwiftToCLR right now, and hopefully I’ll be able to chip away at those as time goes on. If this project can push things in a positive direction even slightly, I’ll consider that a huge bonus.

If you find this project interesting, please do head over the the GitHub repository and take a look. The readme there goes a lot more in-depth to the technical details of this thing, and contains instructions for compiling and diving into the code yourself — everything mentioned above is open-source.

As always, I’m @iKenndac on Mastodon and am happy to chat there (although please do note my policy of ignoring unsolicited private mentions — talk to me in public!) about this — especially if you’re experienced with any of the approaches taken here. I’d love to hear your feedback!

Special Thanks

I’d like to thank a couple of folks who’ve been particularly inspiring and helpful for this project. They’ve helped me navigate a tricky and unbeaten path, for which I’m very grateful:

-

Michael Thomas: This whole thing started when I saw a post of his on Mastodon that pulled a thread in my mind that cost me a new laptop and over a month of my life. I do love the laptop, though, and this project has been a ton of fun.

-

Brian Michel works at The Browser Company, and is part of a team building a whole web browser in Swift on Windows! Their approach is different to this one, but equally as interesting. You can see some examples of their work on GitHub.