Secret Diary of a Side Project is a series of posts documenting my journey as I take an app from side project to a full-fledged for-pay product. You can find the introduction to this series of posts here.

In this post, I’m going to talk about some of the mental shifts you need to do when taking the leap from side project to real product.

That pivotal moment. It’s weird. You’ve been looking at this project for months, maybe years, slowly adding code here and there. Features slowly form, and the bugs get less “Oh, don’t push that button — it’ll crash” and more “Yeah, I need to make sure those buttons line up”.

Then, one day, you’ll use it for real. In my case, it was in a photography studio learning about portrait lighting. I was taking a break and wanted to look at some of the pictures I’d taken. I happened to have my iPad with me, so I fired up whatever build of the app I had on there and used it to download some photos from my camera. Then, we passed my iPad around and discussed the merits of my photos and how to improve them.

I read or heard or saw a piece by Wil Shipley a while ago (long enough for the memory to have faded a bit, so apologies if I’m mis-quoting him), where he said he takes “Is that all it does?!” as a compliment, as it means that you’ve made something that ‘clicks’ with the user so well that they can just get on with their task without all the stupid computer things getting in the way.

I had that big-style on that afternoon in the studio. At that point, the app was around 15,000 lines of code, which isn’t tiny to say the least — the main breadwinner from my previous company was 18,000. From a programming point of view what I did is pretty complex task — detecting the camera on the network using their stupid thing that isn’t Bonjour, connecting and handshaking with it, dealing with its finicky protocol, downloading a stupid Canon RAW file to the iPad, converting it to JPG and allowing the user to view it fullscreen.

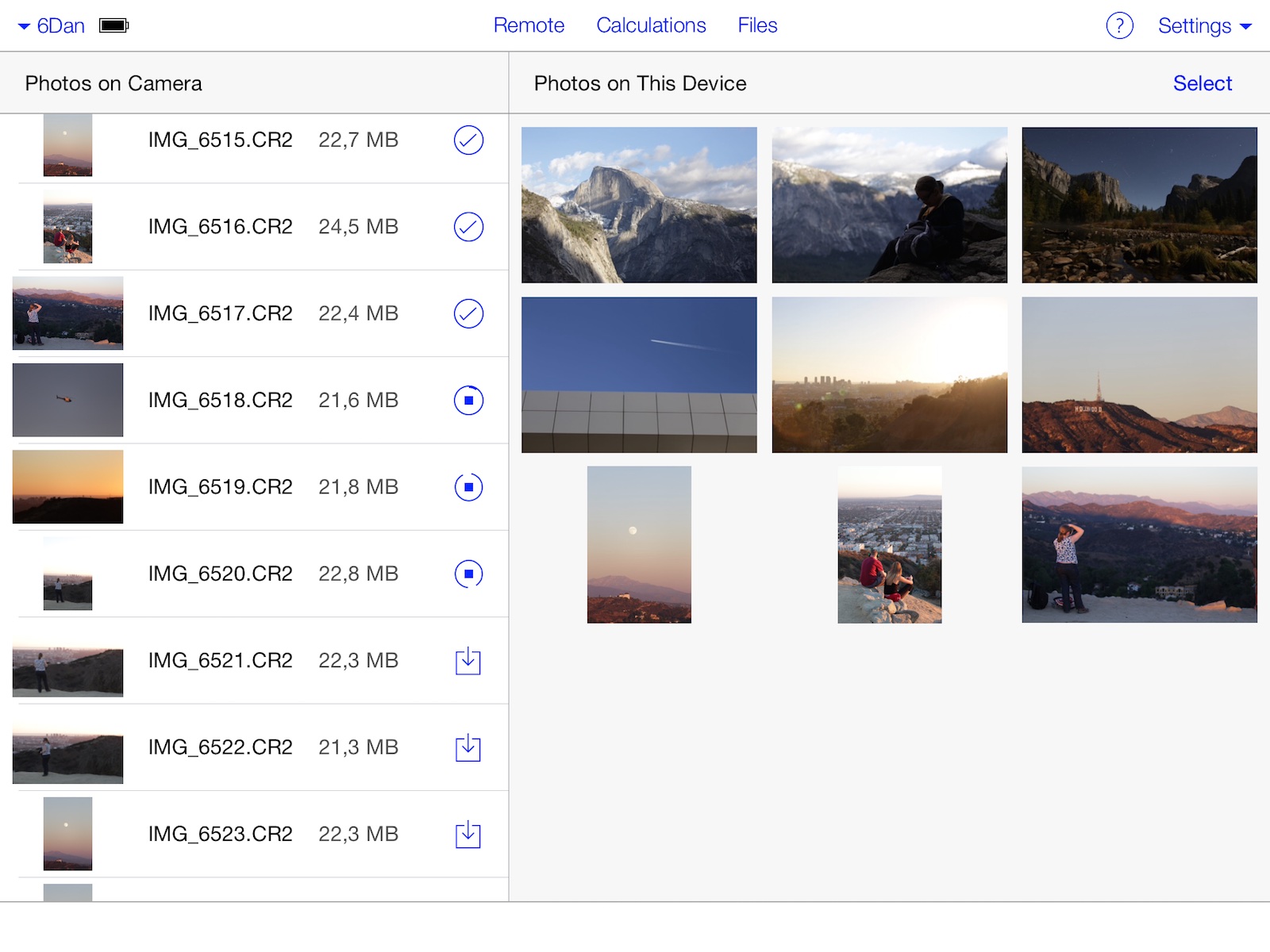

Downloading photos from a WiFi-enabled SLR in an early build of my app.

My app distilled that down to two taps. Three, if you count launching it in the first place. And in this busy place with lots of people wanting to see my picture, it worked flawlessly. I launched the app and it found and connected to my camera and presented the photos within. “Can I see that one?” someone said. I tapped the “Download” icon, watched a progress bar for a few seconds, then tapped the thumbnail that appeared in the “On this Device” pane to view it fullscreen. “Cool!” the guy said “…but I think if you moved the light down a bit, you’d make that shadow softer, which I think would make the photo look nicer.”

At that moment, I felt so proud. This is why I make software. The process was so smooth that it completely melted away into the background, to the point where nobody else even noticed the app. Instead of spending time using my app, we spent time learning about studio lighting.

Evidently I missed the “Try not to look like a scruffy hobo” preparation step of going to a studio.

That day, my project shed its “side project” status and became a thing I knew could be genuinely useful to people. I’d been idly considering it for a long time, but I knew that I should try to finish this and ship it.

Once this big perception shift has happened, everything changes. It’s really important to take this perception shift seriously and be strict with yourself — if you carry on as before, your side project will stay a side project and you’ll end up shipping something not up-to-scratch.

Before we continue, let’s take a moment to define what a side project actually is:

- The primary attribute that all the others derive from is that it’s a project written in your spare time, which gives extreme time limitations.

- Features are typically written on the path of least resistance, throwing best practices out of the window in the name of getting a feature done in the hour you have before you go to bed.

- Unit tests? Nah. Error checking?

// TODO: Handle this properly

Obviously, these behaviours need to change. So, how do we manage the transition?

Keep Refactoring Strict

As soon as you decide to turn a side project into a real product, it’s very tempting to go back and refactor everything immediately. Rebuild the code! Undo all the shortcuts! Add tests! But, if it works… don’t. Not yet.

You need to be really strict about rebuilding if you ever want to ship the thing. The rule of thumb I follow is: If I ship a build to testers with no changes except this refactor, will they notice? Sometimes the answer will be “yes”, and if that’s really the case then go ahead. However, if the answer is “no”, think hard before touching that code.

An example of this is the library that actually speaks to the camera in my app. It has three layers — the outer layer defines a very generic API for the application to consume. “Take a picture please”, “List the files on the memory card”, etc. The middle layer defines slightly lower-down APIs, but still fairly generic. “Send this command with these parameters, then give me the response here”-type stuff. Basically RPC. Finally, the very-internal layer actually deals with the grunt work of encoding the binary messages properly, handling responses and dealing with the upkeep of keeping the camera happy.

These three layers work in concert so the application doesn’t have to care about the workings of the camera at all. I’m actually pretty pleased with the design of most of it.

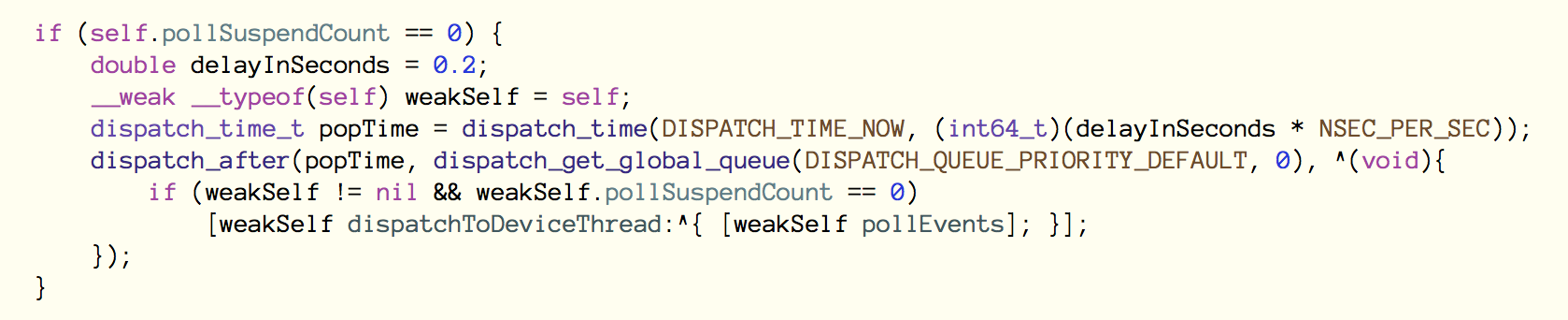

However, that inner layer. The most important one. The most intricate one, dealing with TCP sockets and threads and all that fun stuff. It’s terrible from a code-style point-of-view.

However! It works, and it works well. The last commit on that class was in June 2014, adding a minor feature. Before that, I last touched the code in July 2013!

I must’ve been severely sleep-deprived when I wrote this glorious mess. But, it works, so it stays.

As an engineer, I would love to refactor that class. I could redesign the shit out of it — it’d be a work of art! However, by now that class must have handled over a million commands to and from cameras in my care, and it just plain works. That code is over a year and a half old, and now this project is a real product with a release looming in the not-too-distant future, it just doesn’t make sense to mess with it.

…and Do It Right When You Do

Alright, so it’s time to refactor some code from the side project era. Make sure you do it right — design it properly, add tests, etc. Replacing some old crappy code with slightly less crappy code that hasn’t been thought through or tested properly isn’t worth the effort.

A Commit A Day…

I got this tip from Simon Wolf: do something on your project every single day, no matter how big or small. I started doing this and bar my honeymoon, I’ve kept up with it pretty well. Sometimes (like today) all I do is tweak the in-progress website a bit. Yesterday I moved my icons from Photoshop to Sketch. The day before, I spent nearly 11 hours working on an advanced feature.

Every time you touch your project in any way, unless you’re doing it very wrong, it’s getting better. It might only be a tiny bit better, but it’s getting better.

Over a year’s worth of tiny bit betters and my project is pretty damn mature.

Keep Away From New Shiny

Remember: This is a real product now. If you bring in every shiny new library or even language that comes along, you’ll end up spending hours working and not moving forward at best, and end up with a half-working project that has hundreds of dependencies at worst.

This Is Starting To Feel Like Work!

These restrictions take away a lot of the fun things about side projects. This can be a little discouraging at first, but stick with it. You’ll (hopefully) start to find joy in the results of your work rather than the process of making it. Sure, mucking around with autolayout for hours is a pain in the ass, but just look at that UI! It’s glorious!

Next time on Secret Diary of a Side Project, we’ll talk about some actual software development practices and idioms that’ve helped me. There’ll be code and everything!