I’m an old Mac-head at heart, and I’ve been using Macs since the mid 1990s (the first Mac I used was an LC II with System 7.1 installed on it). I don’t tend to genuinely think that the computing experience was better in the olden days — sure, there’s a thing to be said about the simplicity of older software, but most of my fondness for those days is nostalgia.

For example, I have wonderful memories of finally getting a copy of ClarisWorks and being able to do pixel-based image editing, which sparked a wonderful childhood “career” of tinkering with icons and various other bits and bobs with that and ResEdit. The things you could do before code signing!

However, I’m not going to sit here and say with a straight face that ClarisWorks on System 7 in the 1990s was better than using the myriad of tools we have available to us today. It’s nostalgia for a simpler time — both in computing, and in my life.

An exception to that, however, is Apple’s Aperture. I’m still grumpy that Apple discontinued it back in 2015, and I’m not alone. Start spending time in the online photography sphere and you’ll start to notice a small but undeniable undercurrent of lament of its loss to this day. Find an article about Adobe hiking their subscription prices because they added AI for some reason, and amongst the complaining in the comments you’ll invariably find it: “I miss Aperture.”

![]()

Aperture’s icon.

A couple of things have happened recently that spurred me to actually write all of this down rather than grumble occasionally on social media:

-

Apple released macOS Tahoe, which has been pretty constantly raked over the coals for poor design and broken interactions from the day it was released (and even before, if we’re honest).

-

Apple very recently announced their Creator Studio subscription service, and I saw this post on Mastodon by @BasicAppleGuy:

When I took this screenshot, the first reply to the post was “I miss Aperture. <long digital sigh>”.

So, I dug out the ‘ol Trashcan Mac Pro I lovingly reviewed here on this very blog over eleven years ago and fired up Aperture to document — at least partially — just why it was so special.

The Mac Studio is a perfectly cromulent computer, but it just doesn’t have the verve of the classics, you know?

So, Why Is Aperture So Special?

If you’re not familiar with Aperture, it’s an app for organising, managing, editing, and exporting images. If you’re familiar with Apple’s Photos app, it’s that. But for professionals! Aperture is a complex app — its PDF user manual is over 900 pages long — so to keep this manageable I’ll focus on one particular aspect of it via two short excerpts from said manual.

Two excerpts that hide an astonishing amount of engineering effort.

Let’s look at our first excerpt:

To work efficiently in Aperture, you can use floating windows of controls called heads-up displays (HUDs) to modify images.

This little sentence extremely succinctly describes how Aperture is different to most other software of its nature — it comes to you. Most software has you go to it.

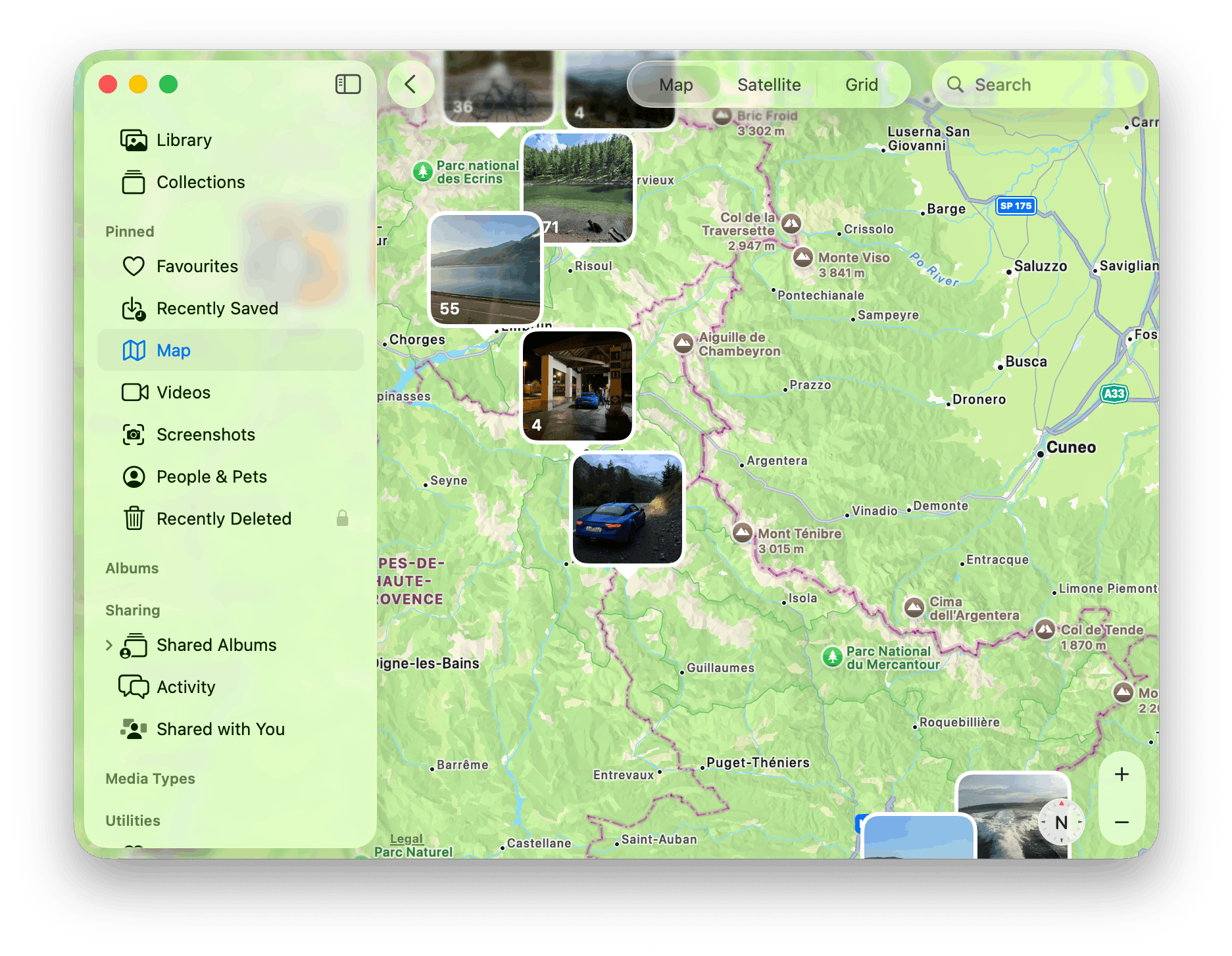

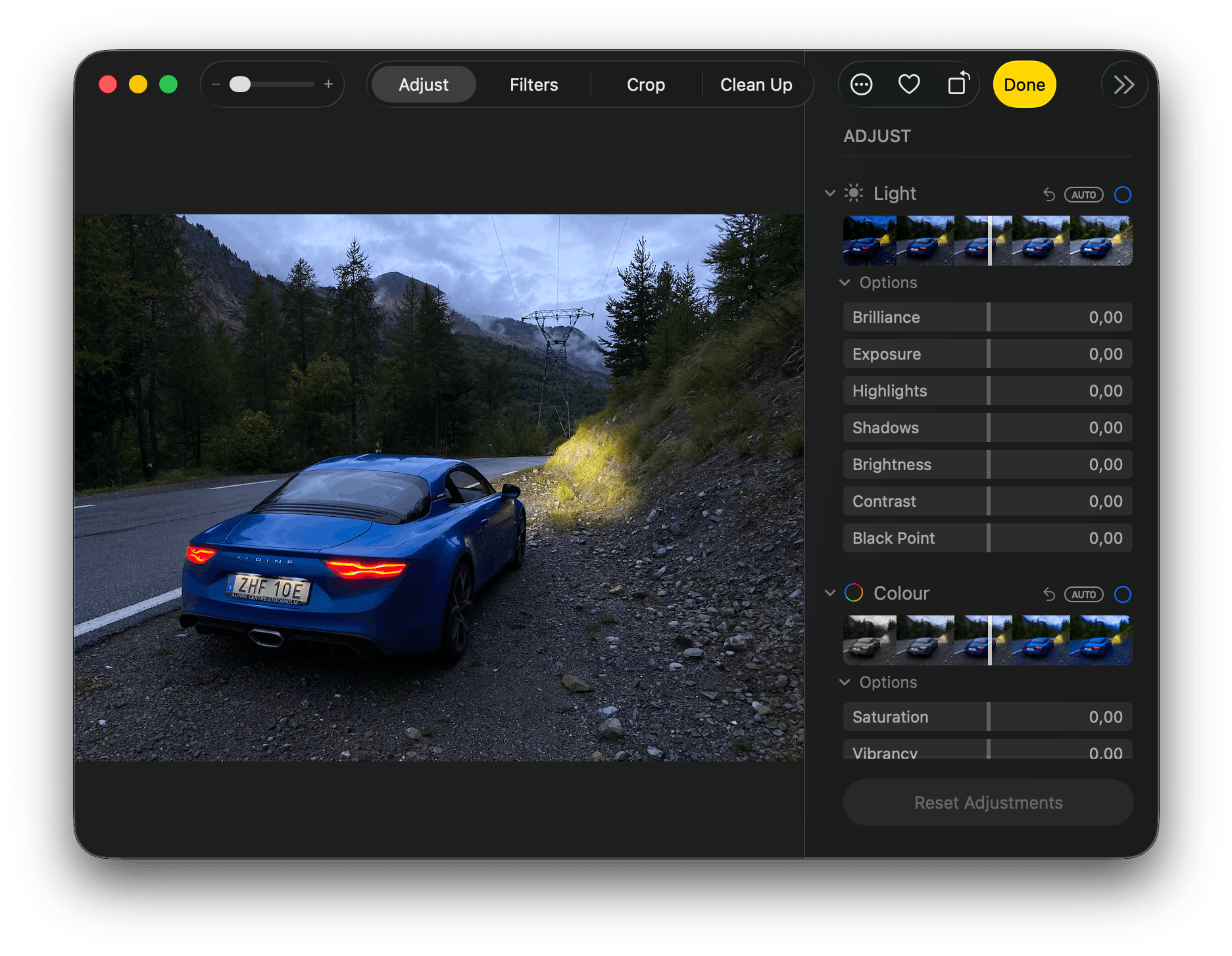

To understand what I mean, let’s look at the Photos app. My brain works pretty spatially — I remember where I took a photo more than when. So, I pan around the map in Photos to find the cool photo of my car in the Alps that I want to edit and send to my friend. Here it is:

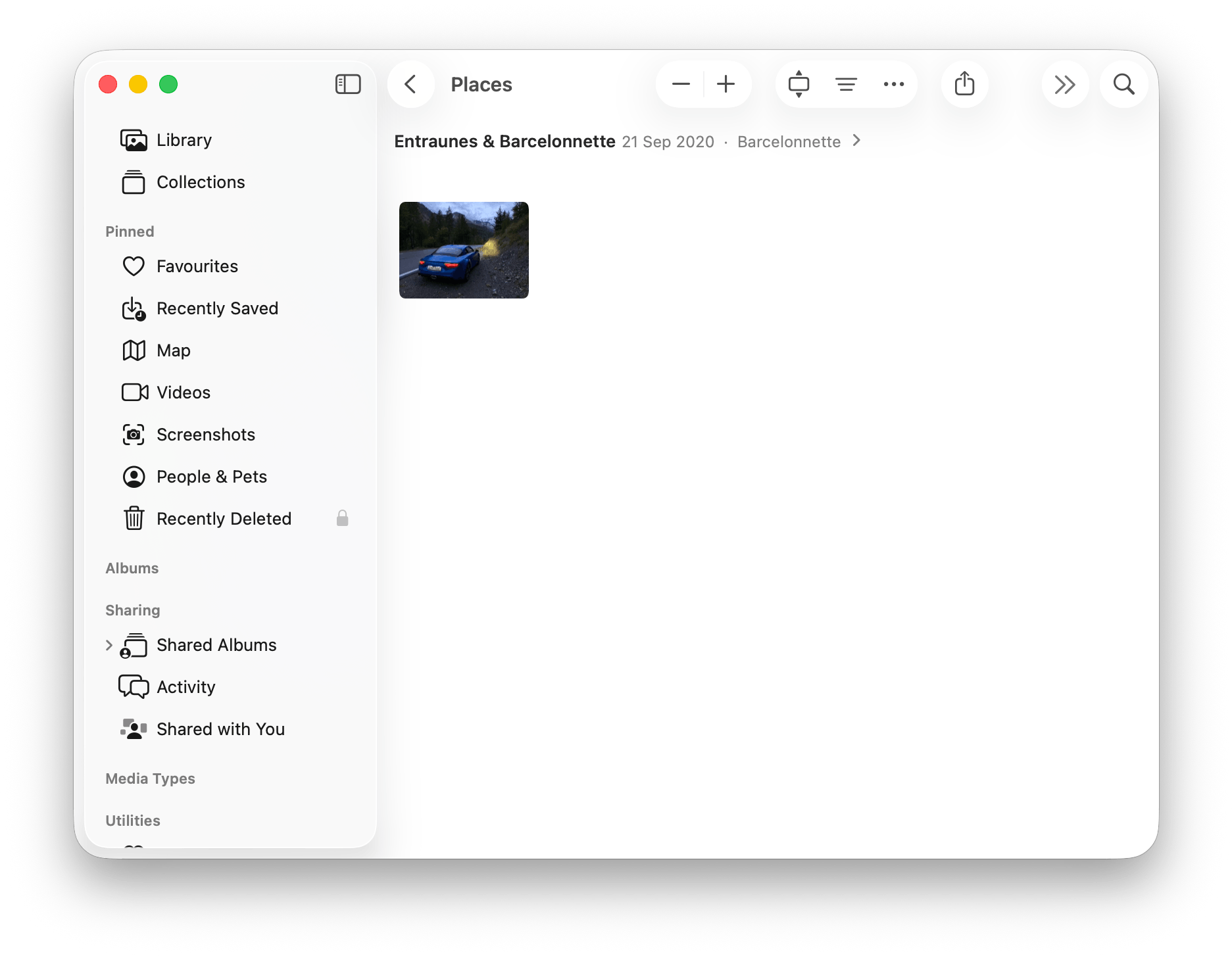

I click the picture, and the map is gone, replaced with a list of the images at the location I clicked.

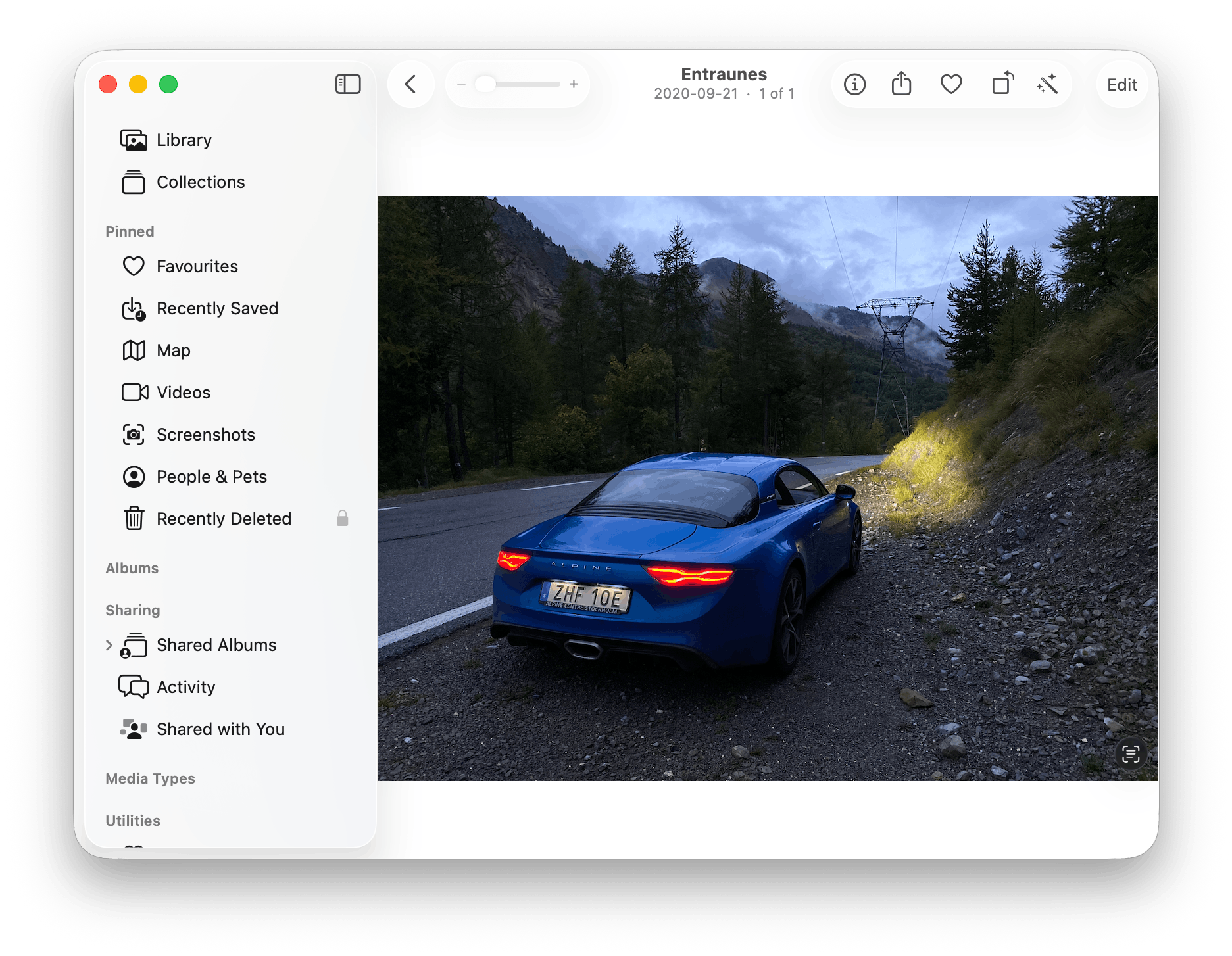

I double-click the photo to bring it up bigger.

I click “Edit” in the top right of the window to switch into Photos’ editing mode (as a shortcut, I could’ve pressed the Return key in the image list to open it straight in the editing mode).

I perform my edits, then click “Done” to get back to the fullscreen viewer. Then I click “Back” to get back to the list of images. Then “Back” again, and I’m finally back at my map. Hooray! Oh wait, I forgot to export it…

This sort of design is common in apps like Photos, and especially in “shoebox” apps1. Every feature is in its own place, and if you want to use that feature you need to pick up your thing (in this case, a photo) and take it over to where the feature is. In this example, the journey from the map to the editor is through a separate list of images, the fullscreen viewer, then finally to the editor.

In contrast, Aperture comes to you. As a reminder:

To work efficiently in Aperture, you can use floating windows of controls called heads-up displays (HUDs) to modify images.

When Aperture says this, it really means it. If you can select an image, you can edit it right where you are with that HUD.

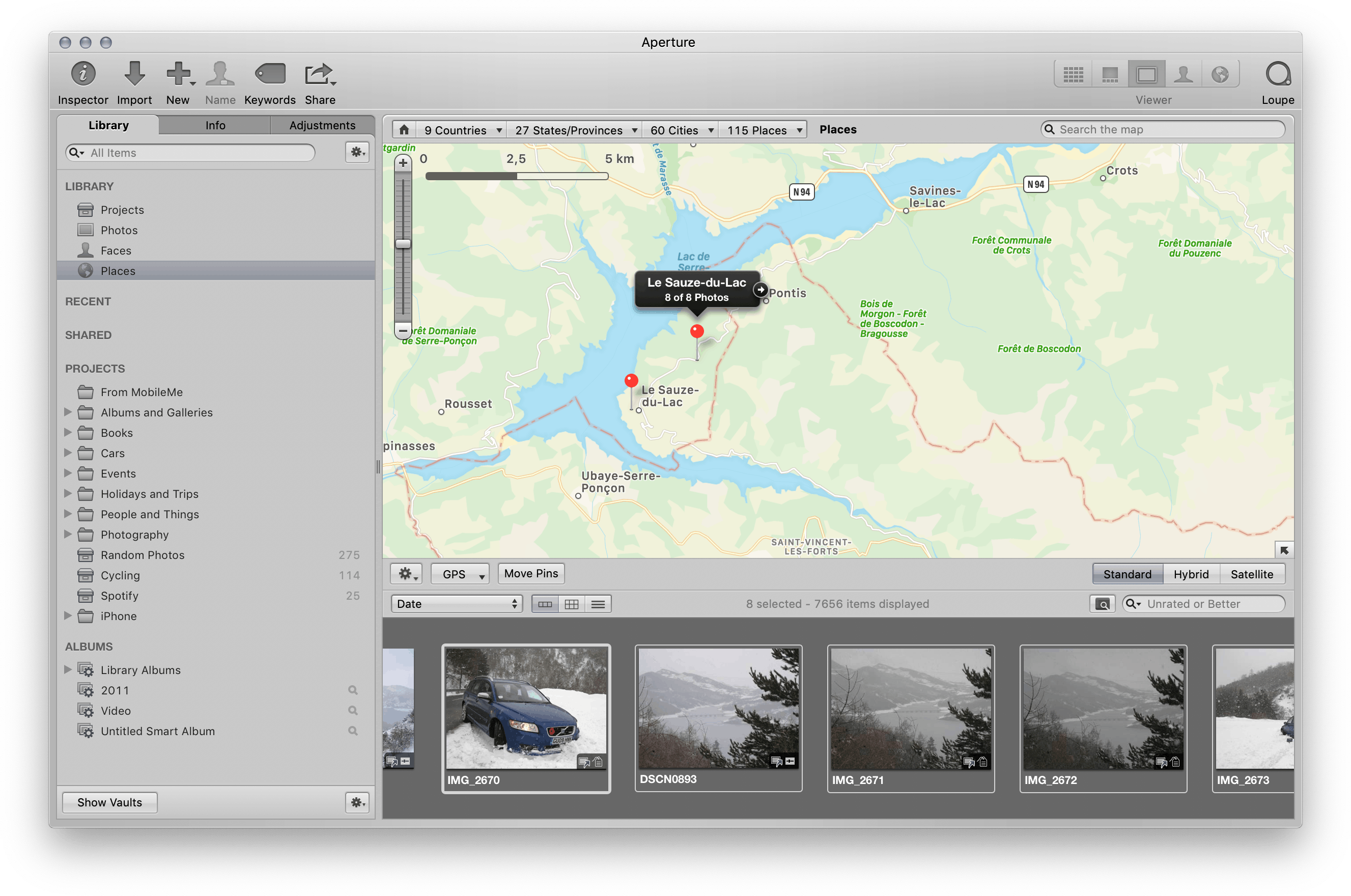

Aperture’s map (which by some miracle still works eleven years after it was discontinued) doesn’t show the images on the map, but rather underneath it. It’s less pretty, but combines the first two steps of the journey in the Photos example — the map on top, and the images in the visible map area underneath. Clicking a pin refines the selection of images.

Alight, let’s find another photo of my car in the Alps:

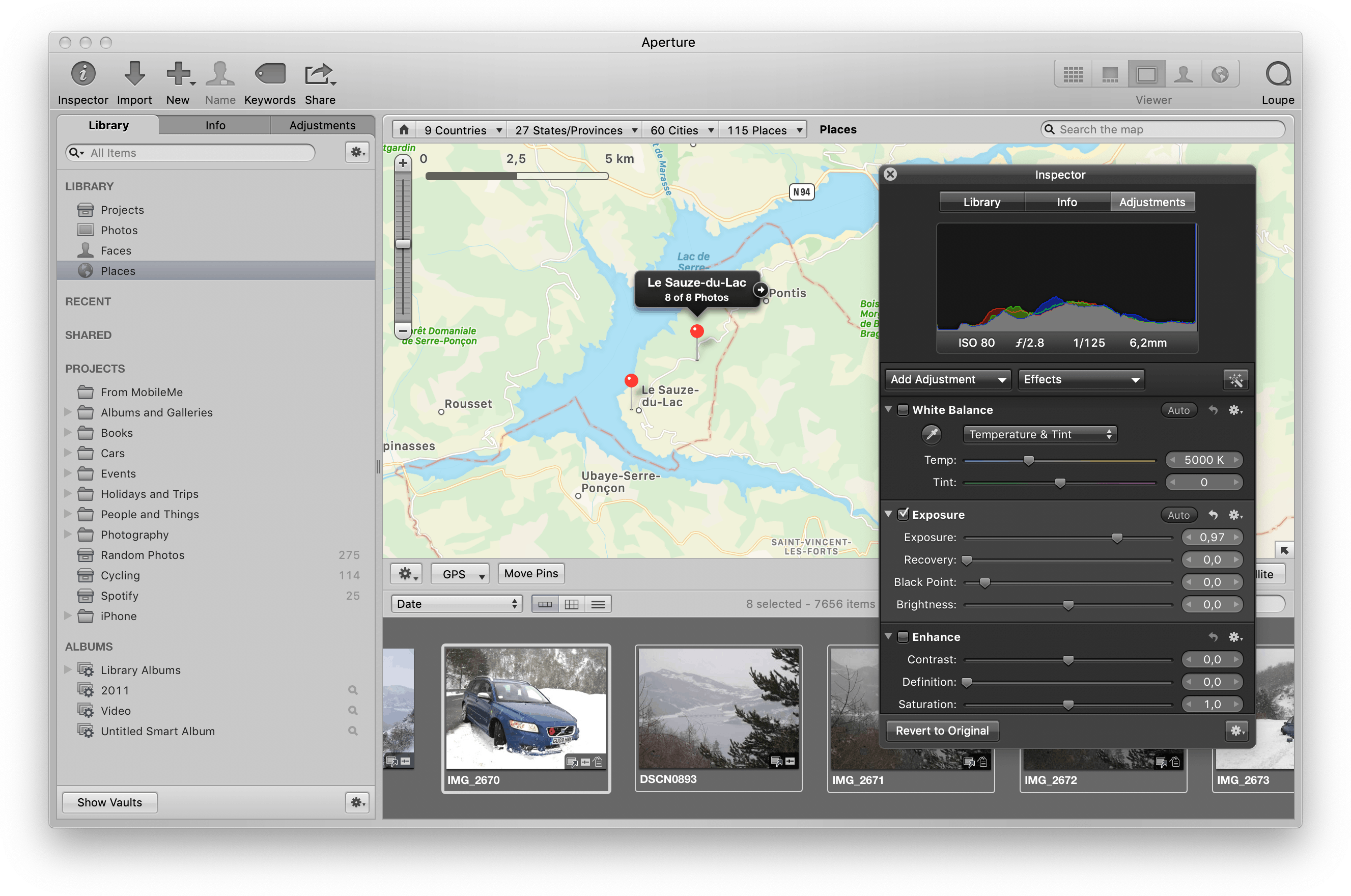

A Volvo stuck in the snow is less awesome than the previous photo, but oh well. I need to edit it, so I press H on my keyboard to bring up the adjustments HUD. I’m still exactly where I was, but now I have editing controls. There’s no step three!

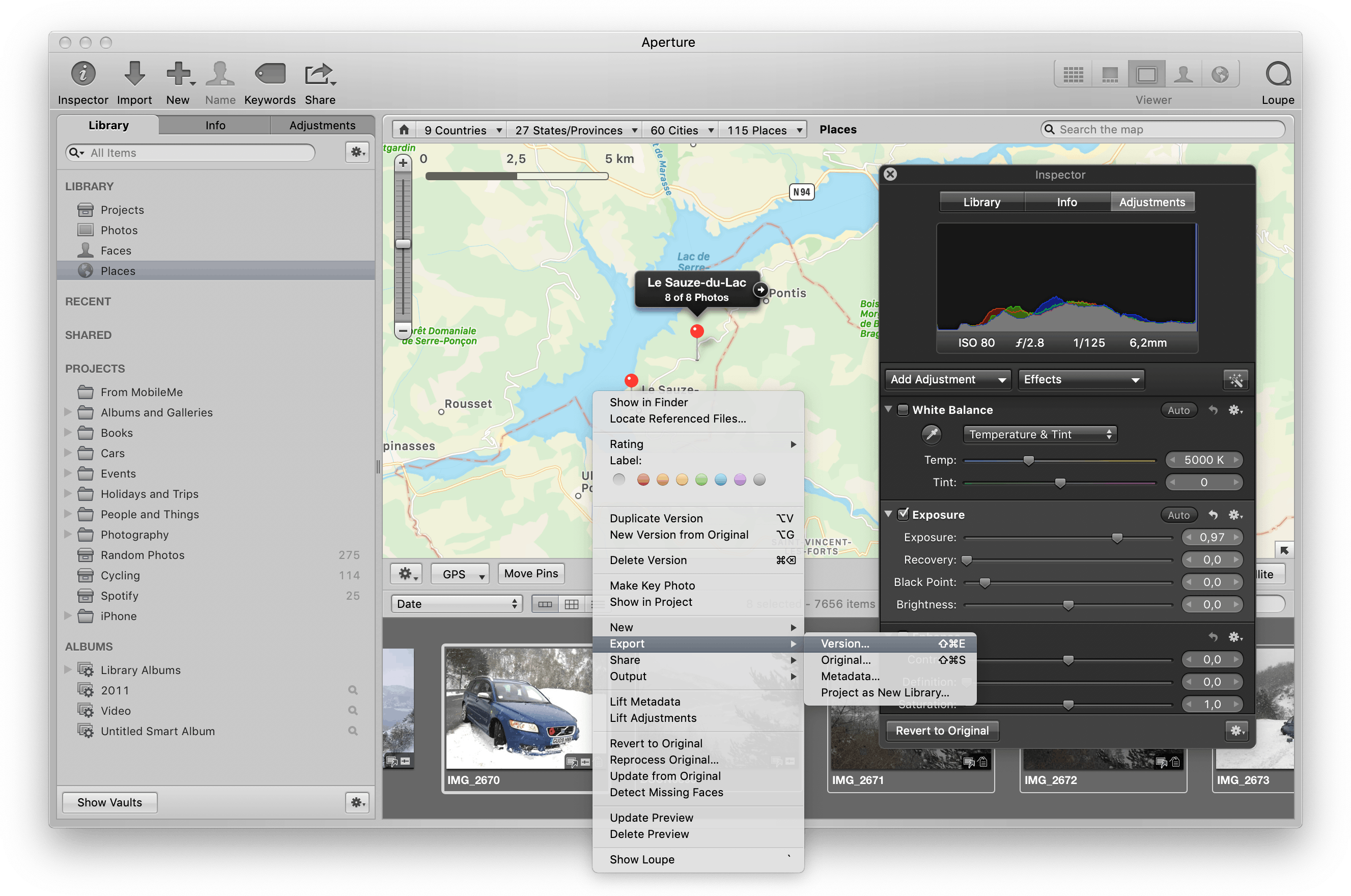

That was incredibly easy, and I didn’t even leave the map! I need to export it now… and, of course, I can do that from right here on the map too.

I’m still exactly where I was, and I can carry on with the next task.

“But Daniel,” I hear you cry, “Who edits photos on a map?”

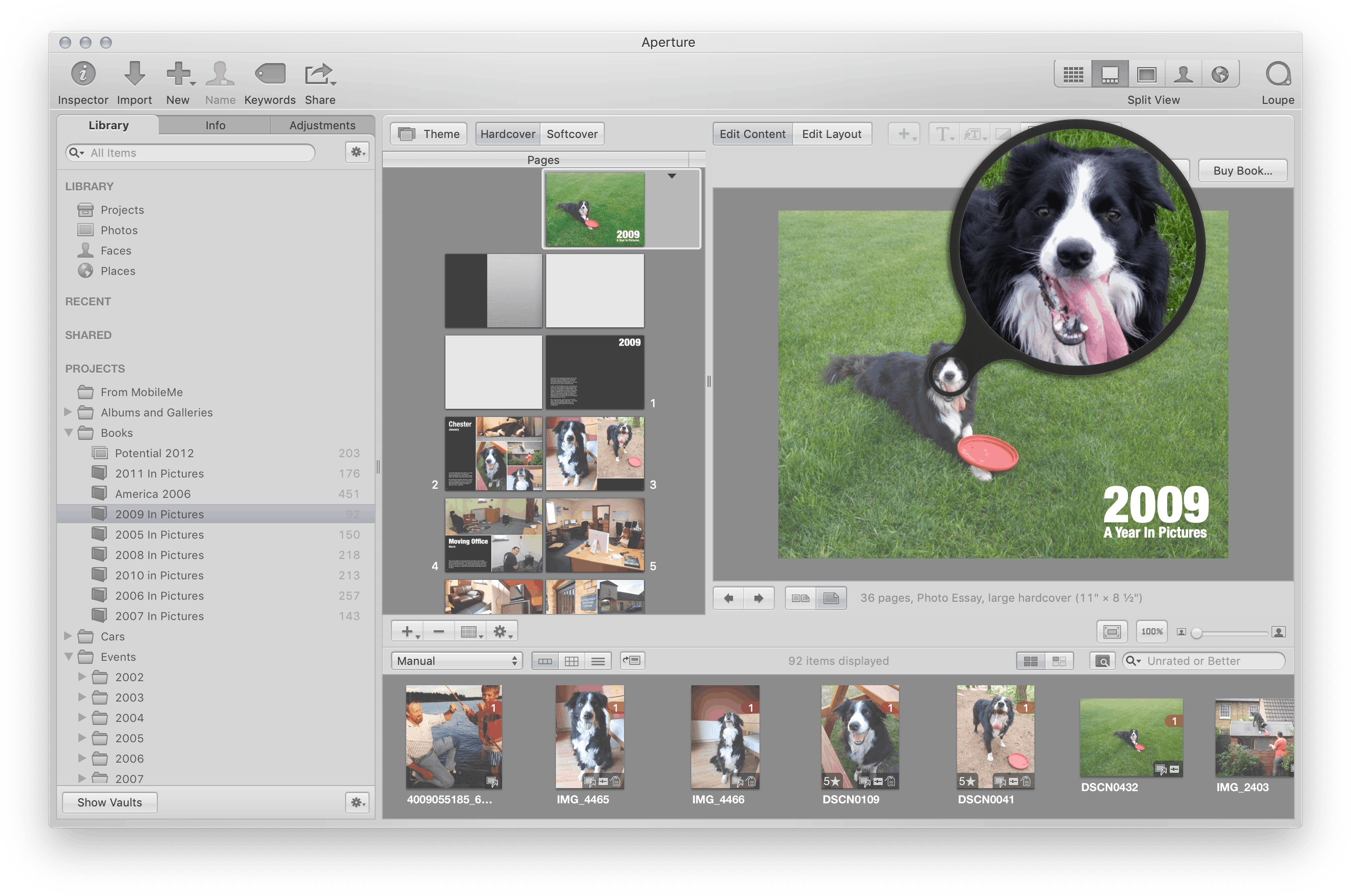

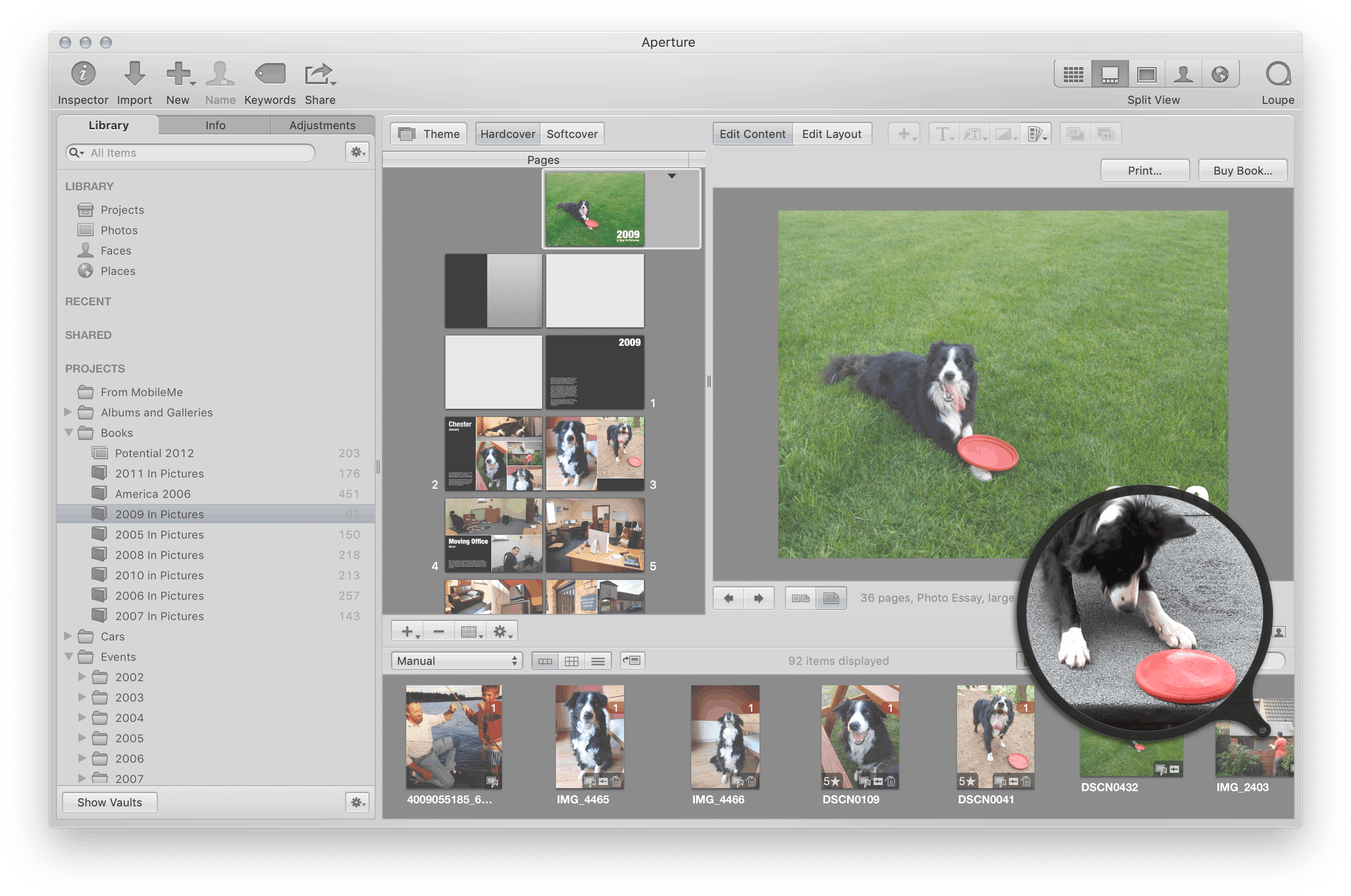

Fine, it’s a contrived example, but one I was able to directly make between Photos and Aperture. Let’s look at something more real-world: Aperture’s book editor. I love making photo books as the years go by, but putting them together can be a long and tedious process.

Let’s imagine it’s 2005, and I have a page in my book full of pictures of my new car for this year’s book. Unfortunately, auto white balance and changing lighting conditions means the car is a different shade of grey in every photo! Disaster!

It’d be nice to have them consistent with each other on the page, but matching them all together when they might be from all over the photo library is a big pain. Can you imagine doing that in Photos? Click, click, click, click, into the editor. Tweak white balance. Click, click, click, click, back to the book. Nope, still not right. Click, click, click, click…

To work efficiently in Aperture, you can use floating windows of controls called heads-up displays (HUDs) to modify images.

Oh, right! H, drag slider, done. Right on the book page.

It’s hard to overstate quite how revolutionary and smooth this flow is until you had it for multiple years before having it taken away. Nothing on the market — even over a decade later — is this good at meeting you where you are and not interrupting your flow.

Especially that book example. My Lord. When Aperture was discontinued (well, when it stopped working properly after an OS update or two) I moved over to Adobe Lightroom (now Lightroom Classic) which had separate modules for file management, editing, and books — switching modules was such a slow and clunky processes, I swear nearly threw my computer out the window trying to colour match photos on a book page.

It’s OK, Daniel, you got rid of Lightroom years ago. It can’t hurt you any more!

Technically speaking, the edit-anywhere model is an incredibly impressive feature. Managing a lot of images is already difficult2 (especially on the hardware of the time), and for a map, or a book editor… of course you’d have an optimised set of static thumbnails.

Or, y’know, a full RAW image editing context ready-to-go for anything you might want to click on.

Alright, Now They’re Just Showing Off

Aperture has a tool called the “loupe”. In real life, a loupe is a little cup with a magnifying glass on the top. It’s what’s on the Preview app’s icon, and you use it to zoom in to physical things on a physical surface (I know, how quaint).

Back to the manual:

If you want to quickly check specific compositional details of an image, you can use the Loupe. Aperture provides a software Loupe that lets you magnify portions of an image. The Loupe is particularly useful when you are quickly navigating through images in the Browser and you need to verify that the image is in focus or other details without having to switch to the Viewer or Full Screen view.

In Aperture, the loupe is a little round zoomy thing you can either drag around to view a zoomed-in portion of the image it’s on top of, or attach to the mouse so you can just point at stuff to zoom in.

Note: I’ve dimmed the main Aperture window slightly in the following screenshots to make the loupe clearer.

Fun fact: Even when attached to the mouse, the loupe is a separate window just like the other HUDs — which means you can take a screenshot of it independently. Neat!

It’d be easy to think this is just a screen zoom, or at least a window into a big thumbnail that’s being downsampled a bit for the main viewer. But, since the loupe is attached to the mouse, we can just start pointing at stuff to see what happens.

There’s no way you’d keep a full-resolution image in memory for every thumbnail on screen, so this is another extremely impressive technical feat. Remember, this is over a decade ago, and Aperture’s system requirements were a Mac with 2GB of RAM. Keeping a whole 20 megapixel image in memory will consume somewhere in the region of 90-120MB3 once you’re starting to display it.

Hmm… now that I think about it, the manual doesn’t say where the loupe works and doesn’t, and since we’re not limited to selecting images like with the other HUD…

🤯🤯🤯

Once again, it’s hard to overstate how bonkers this is on a technical level. That’s a list of thumbnails of book pages, there so you can identify which page you want to edit. That thumbnail-within-a-thumbanail — on a Retina display! — is 68x47 pixels. 0.003 megapixels.

From a software development perspective, it would be insane to have those pages be anything but static thumbnail images. But hey, would you want to be the person that made the manual say that the loupe works everywhere except in the book editor’s page list?

Conclusion

These days, technological marvels in computing — if you’ll forgive a gross generalisation — tend to be very flashy. Liquid Glass is a great example of that — it’s very impressive what can be done with the engineering talent and computing power we have available to us today, and the effect is cool. However, my browser’s UI refracting the webpage I’m reading as it scrolls by doesn’t really do anything except look cool… when it isn’t making things less readable.

Notice how the Liquid Glass refraction effect makes it look — at first glance, at least — like we’ll be making a sharp right after we turn left? Thanks, Liquid Glass!

Generative AI is another technology that falls into this “flashy” camp, but kinda at the other end of the scale. BEHOLD THE AI, FOR IT IS PRODUCING CONTENT. Very useful, very impressive, and is transforming a lot of industries. Just… ignore the wider societal and environmental concerns AS THE AI IS PRODUCING A FUNNY POEM.

It’s easy to dismiss criticisms of these kinds of technologies as the ramblings of an old man, since on average — as I mentioned at the top of this post — the computing experience is orders of magnitude better than it was back then.

However, when it gets to the point where we as humans need to use our computers as tools to get stuff done, I think we have stagnated over the past few years. When preparing for this post I was excited to fire up Aperture and experience it again, but after less than ten minutes of using it I was getting grumpy — here I am, sitting at a thirteen-year old computer, and I’m flying through my photos faster than I ever do on modern machines. Why is this not possible now?

Aperture’s technical brilliance is remarkable in how quiet it is. There’s no BEHOLD RAINBOW SPARKLE ANIMATIONS WHILE THE AI MAKES AUNT JANICE LOOK LIKE AN ANTHROPOMORPHISED CARROT, just an understated dedication to making the tool you’re using work for you in exactly the way you want to work.

It’s the kind of monumental engineering effort that the user is unlikely to ever notice, simply because of how obvious it is to use — if I want to zoom in to this photo, I point at it with the zoom thing. Duh. Sure, it’s a tiny thumbnail inside a small thumbnail of a page in a book… but how else would it work?

And that is why Aperture was so special. It was powered by some of the most impressive technology around at the time, but you’d never even know it because you were too busy getting shit done.

And then, it was taken away — with a final, cruel twist of the knife from Apple: “You can use the Photos app as a replacement!” — and everyone was grumpy forever.

Bonus Anecdote!

Aperture’s discontinuation happened at the tail end of my time working at Spotify here in Sweden. As with any corporate job, it had good days and bad days… and after the particularly bad days, I’d rage-fill part of a job application elsewhere. I’d always loved Aperture — as a Mac developer, it was the pinnacle of what was possible on the Mac, and in a field I was passionate about — so this particular application was to work on Aperture at Apple.

I ended up having a couple of interviews with the Aperture team, but as I remember (this was well over a decade ago) the process just… kinda petered out.

A few months later, the official discontinuation announcement happened. I have no idea if I was just not up to the task or if something happened internally during my interview process, but it’s an interesting “What if…” to think about.

Further Reading

-

Aperture: Senior QA (2004-2005) by Chris Hynes

While the result was amazing, the development process was… perhaps less so. This is an interesting read about Aperture’s development. -

It’s hard to justify Tahoe icons by Nikita Prokopov

A great look on why (amongst many other reasons) macOS Tahoe is being raked through the coals at the moment.

-

“Shoebox” apps are apps that contain the content you use with them, as opposed to document-based apps which work with content you manage as a user. It’s an extremely common design nowadays, but less so back then — early pioneers of the shoebox app were iPhoto, iMovie, etc. ↩

-

I maintain that one of the most technically impressive app on an iPhone is the Photos app’s thumbnail grid – being able to scroll that many images that smoothly is very hard. ↩

-

Maths: 20 million pixels at 12-16 bits per channel. Doesn’t include overheads of getting from the encoded RAW to a GPU-ready pixel buffer. ↩